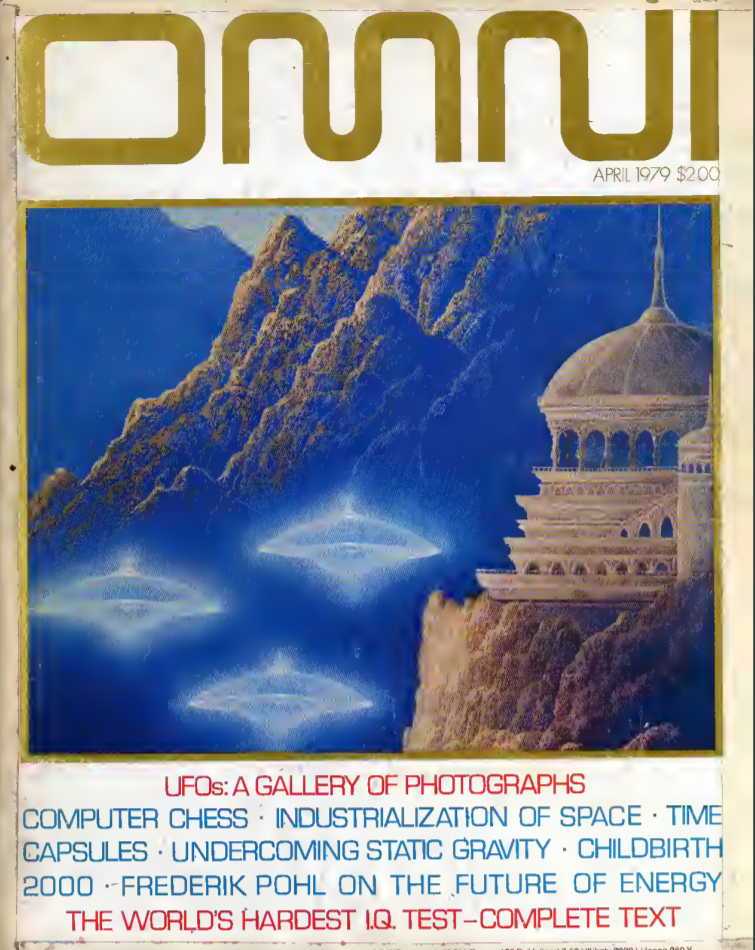

Kevin Langdon's 'Omni' IQ test

First published in the April 1979 edition of Omni magazine in an article by Scot Morris.

Why have I bothered to reproduce this test? - This IQ test was fascinating to me because there is no time limit. Kevin Langdon created a beautiful set of questions that are obviously 'quite hard' - hard enough to need considerable time to answer. His test was intended to be a thorough test of logical problem-solving ability, rather than factual memory, speed-thinking, general knowledge or literary learning.

More info

Standard IQ tests, such as the famous Stanford-Binet scale, are usually time-limited and designed to measure scores clustering around 100, the average in the human population. Unsurprisingly, there is also considerable interest in tests targeted at a higher IQ range - for example see Darryl Miyaguchi's compilation at Uncommonly Difficult IQ tests.

The test reproduced here was designed in 1979 by

San Fransisco systems analyst Kevin Langdon to measure IQs in

the range 125 to 180, and was claimed at that time to be the world's most difficult IQ test. It is unsupervised and

untimed. The only rule was that

you were honour-bound to take it on your own, without help,

but you could spend as long as you wanted on it - hours, days or months. What mattered

was not the time taken,

nor any special expertise

or knowledge you may have, but just your power of concentration and ability to find the only logical solution

by thinking deeply.

When this test was first published, those brave enough to try it sent their completed answer sheet to Omni for marking, and received an IQ report in return. The correct answers were not revealed. This raises an interesting question as to who decides when an answer is correct at this high level. The designer would presumably aim to design each question so that the correct solution, when properly understood, is self-evidently the only possible solution: simple, unambiguous, elegant and satisfying. Then the quiz-taker can also be confident that they have found the right answer, just as with a clever cryptic crossword clue.

Way back in 1979, after a month of concentrated deliberation, I sent

in my score sheet and received a reply saying my IQ was 169. That

sounds impressive, but only corresponds to being 1 in 100,000

persons. At the time I wasn't sure of the answers to about 6 of the

56 test questions so I had to make an educated guess, eliminating

those multiple choice answers that were obviously wrong. After looking again in 2019 after

40 years of subconscious deliberations, ha ha, and also owing to

more recent correspondence with a select few minds**, I now have satisfying

answers for almost all the questions, each with a high probability

of being the same as Langdon's unpublished answers.

**Special thanks to Ken Takekoshi - for

general discussions and to Brian Matthews - for finally eliminating

my long-standing blind spot over Q47.

In the original scoring method, in order to counteract the possibility of guessing (with a 20% chance of being right for each multiple choice question) a 'raw score' is computed equal to the number of correct answers minus one fourth of the wrong answers. Barring statistical variations, this means a set of all-guessed answers would score zero and a set of all-correct answers would score 56.

This test has not been marked by Langdon for

many years. Out of respect for the spirit of the original, I do not

wish to reveal my own set of answers. It has been pointed out to me

that some of the answers have been circulating on the web for

decades. Furthermore, with an accumulation of age and hopefully

wisdom, I no longer consider IQ to be a crucial virtue.

Nevertheless

you can still test yourself for fun (yeah right - fun!)... and I have been

known to compare a submitted set of answers with my own well-honed set to

estimate a raw score for you.

Langdon provided a norming document with his original marking sheet, to show how his scores were derived and how they related to standard tests, and also provided some supplementary information later in the May 1980 edition of his Sigma Four magazine. With a few reasonable assumptions and a raw score, you can use these docs to make an estimate of your own IQ.

****************

During my academic life as a research physicist, I often witnessed

races to offer quick solutions to problems arising in our laboratory

brain-storming sessions. I suspect that the usual 'winners' succeeded

via a

strategy (perhaps unconscious) of aiming to be right around only 90%

of the time, and not fretting too much over any

confounding doubts or alternative theories that might delay an

answer. However, to do better - to be right 99% of the time,

those doubts and alternatives need to be

examined, and that takes longer than a snap answer. How often we ended a brain-storming

session all bamboozled into a hasty plan, only to

realise after the meeting had been disbanded, and after further

thought and effort in the lab, that plan A was inherently flawed. Thank God for plan B. ![]()

Still - horses for courses; a good team contains people with a variety of skill sets. What's nice about Langdon's 'Omni' test is that it gives deep thinkers a chance to challenge themselves. I hope you have fun with it.